Romuald Hazoumè reimagines Tradition

As human beings, we have adapted throughout the millennia to see faces in the most mundane places: floating among the clouds, in the backs of the cars as we drive, and even in the plastic bottles we throw away. This phenomenon, called pareidolia, is a defining force of Beninese artist Romuald Hazoumè’s work. Hazoumè uses a variety of discarded plastic bottles and reshapes them into masks by decorating them with materials such as beads, feathers, and raffia. He turns these inanimate scraps of mass consumption and

instills in them a soul through his creative expression.

Romuald Hazoumè was born in 1966 in Porto-Novo, Republic of Benin, where he continues to live and work. Hazoumè comes from a diverse, highly spiritual background: he is the descendant of a babalawo, a prestigious fâ court priest. His family is Catholic, but kept Yoruba practices such as voodoo and the cult of ancestors. Hazoumè was inspired by his multicultural origins, such as the Yoruba masks, but he departs from tradition through his use of unconventional materials and personalization of the masks, rather than making them idealized and universal. About his use of plastic, Hazoumè once stated: “I send back to the West that which belongs to them, which is to say, the refuse of consumer society that invades us every day.”. Hazoumè’s use of plastic is an impactful political statement through which he criticizes the persistence of colonial exploitation and environmental pollution caused by mass consumption.

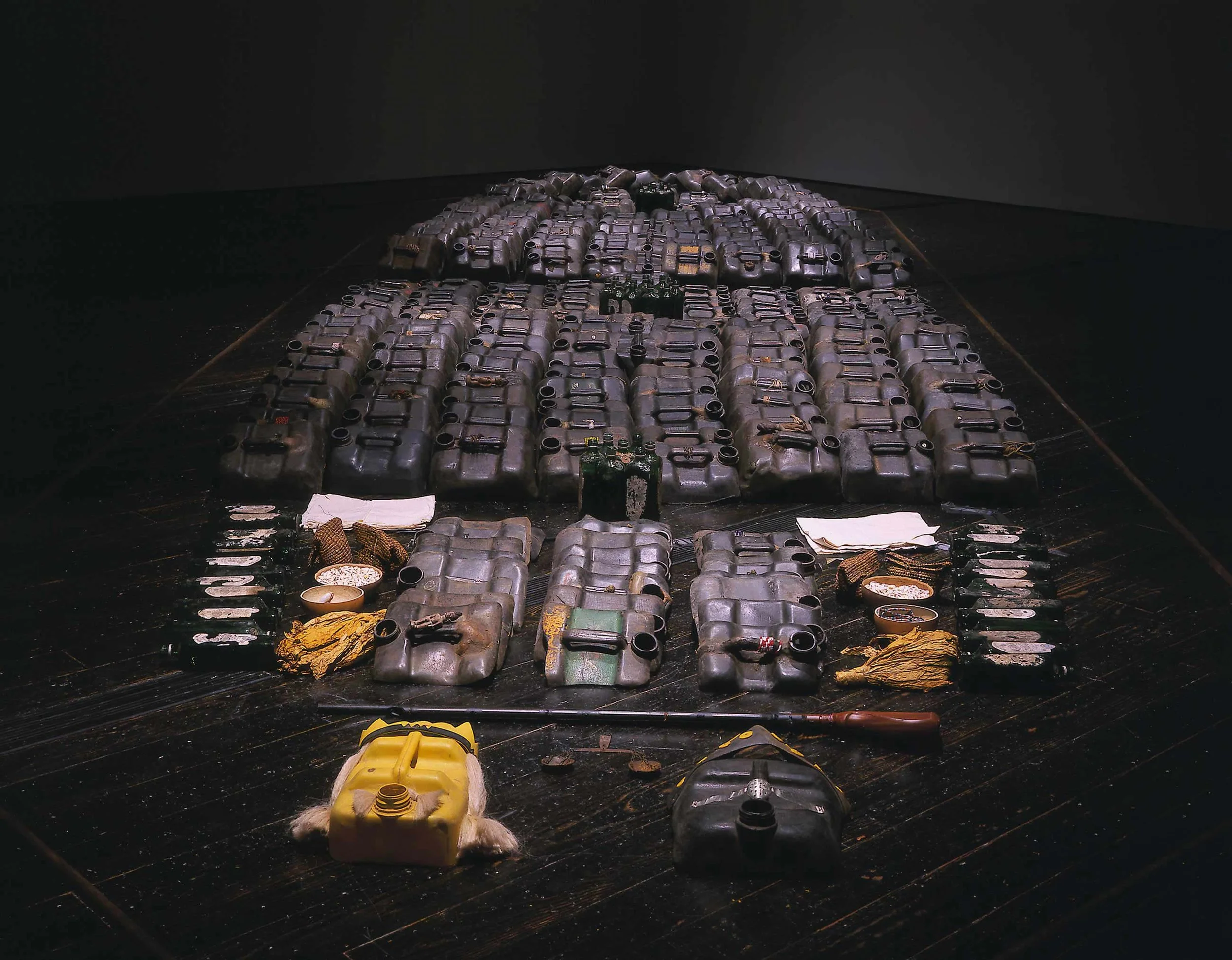

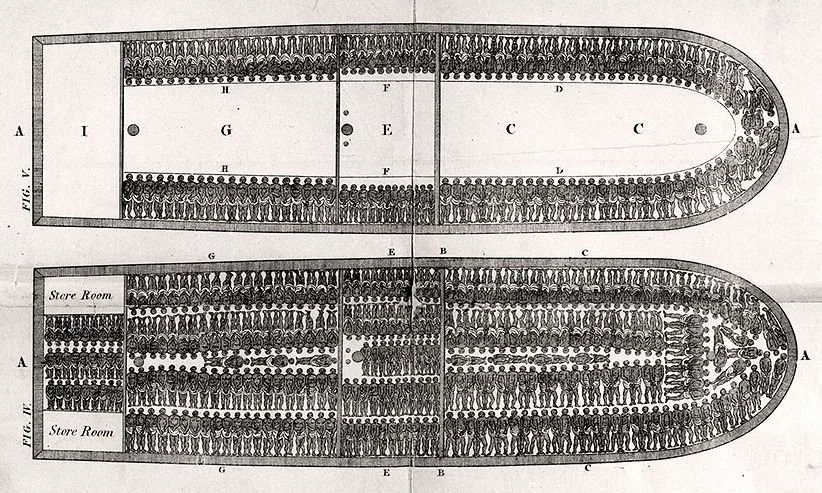

One of Hazoumè’s most notable works is La Bouche du Roi (1997-2005), a multimedia installation made with discarded tops of black plastic canisters cut and decorated to form masks, complimented with a video showcasing contrabandists using the plastic canister to smuggle oil, and photographs depicting traditional dances of Benin. The name of the piece holds historical significance because it references A Boca do Rio, the river’s mouth, which was a key site in the transportation of slaves. The installation’s allusion to slavery is even more explicit in its layout: the plastic bottle-masks are placed tightly next to each other, forming the figure of a slave ship similar to the aerial view of the Brookes depicted by abolitionist Thomas Clarkson. Hazoumè reproduces the sense of confinement and inhumane conditions of these embarkations as the masks seem overwhelmingly crowded, arranged in endless rows representing the enslaved people.

At the very top, there are two key figures: a yellow bottle-mask with a crown and blonde hair symbolizing a European ruler, and a black bottle-mask wearing gold and a crown representing an African ruler. In between them, there is a scale that indicates they have negotiated, as well as a shotgun that suggests this was not a peaceful process. Hazoumè’s utilization of the plastic canisters holds a contemporary relevance to the theme of slavery depicted: the bottles are expanded through the use of fire by motorcyclists to transport greater quantities of oil, to the point that they end up exploding (causing fatal accidents) and lying around as waste, contaminating the environment. The lost bottles, found and repurposed by the artist, draw a parallel with the lives lost in the process of the transatlantic slave trade. It also shows how the appalling legacy of colonialism persists through these clandestine activities, often involving forced labor.

Through his work, Romuald Hazoumè takes abandoned, seemingly worthless discards and imbues them with thousands of years' worth of African artistic tradition. His use of recycled material is not gratuitous; it serves to teach viewers about the current issues in Benin, visualize these problems, and create solutions. Hazoumè’s plastic masks are a testament to humanity’s creativity in making art out of any material, turning mass-produced objects into unique cultural products, and continuing the artistic African legacy of mask-making.

References:

https://www.magnin-a.com/en/artists/14-romuald-hazoume/biography/.

https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/4/article/425385/pdf

Strike Out,

Sofia Ramirez Suarez

Miami

Sofia Ramirez Suarez was born and raised in Caracas, Venezuela and she moved to the United States at 16. She received her Associate in Arts degree at Miami Dade College. She has been published by Miambiance Arts & Literature Magazine Vol. 33 and Strike Miami Issues 6, 7, and 8. She is currently pursuing her Art History Bachelor’s degree at Florida International University. Sofia is passionate about the arts, literature, and pop culture.