INTERMEZZO

My sixteen year old wrists begged to shed their beaded bracelets; they yearned to be traded for a sensible and wise adornment, like a watch. My sixteen year old wrists knew that a grown girl would wear a gold bangle. I look down at my wrists now, and they are plain.

Much like my wrists, my sixteen-year-old feet cried for a shoe with a stiletto heel, green with envy over the click that followed grown girls. Click, click, click down a sidewalk. She is mature. We will meet someday, I thought. I look into my closet today and realize I don’t own stilettos.

I am standing in the middle of adolescence and desire, in between bangles and beads.

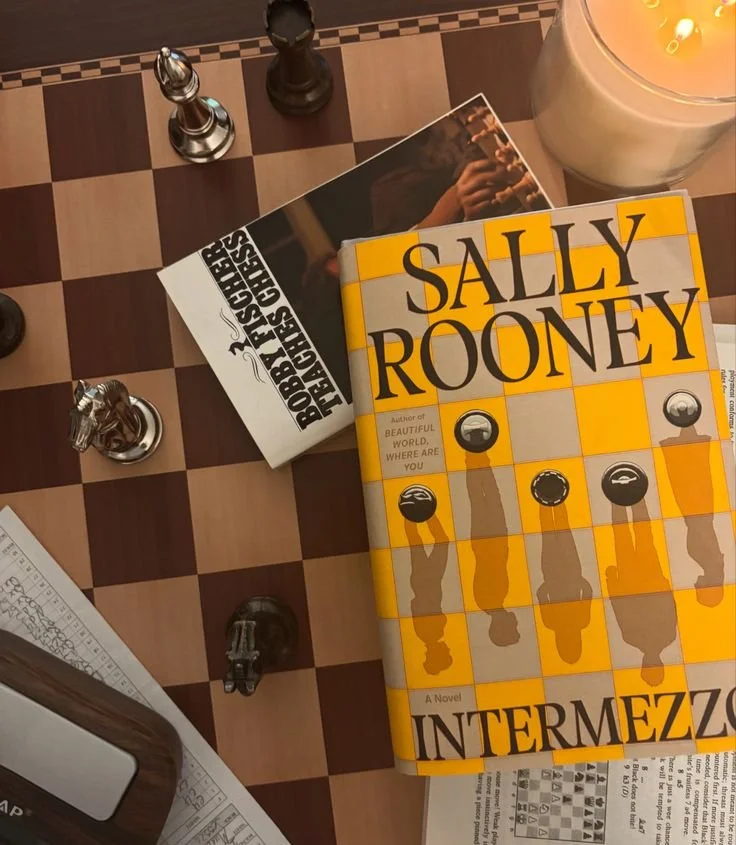

Image Courtesy of Francesca Jaques

It’s written off as a passing phase or an obligatory gap for growth. Everyone feels like this in college. Grasping for twelve things at once, maybe even none—an intermezzo. In the context of Irish writer Sally Rooney’s newest novel, an intermezzo is a tactical “in-between” move in chess. Instead of an opponent responding immediately in an expected way, they insert a surprising move that interrupts the flow of the chess game, forcing you to react first. It’s a pause that shifts the equilibrium and necessitates a new strategy.

Rooney employs this concept as a metaphor to frame the lives of the fictional Koubek brothers, who are suspended between past and future, between their beads and their bangles. The eldest is Peter, a powerful lawyer in his early thirties, and the youngest is Ivan, a twenty-two-year-old former chess player. Peter is condescending and sexy. Ivan is charmingly unsociable. Life played an intermezzo on them by killing their father and forcing them to figure it out. The novel follows their trauma-driven gap year after their father’s death, filled with smaller hardships that serve as intermezzos—pauses that disrupt their flow and remind us how life’s interruptions, both large and small, demand new strategies and reflection.

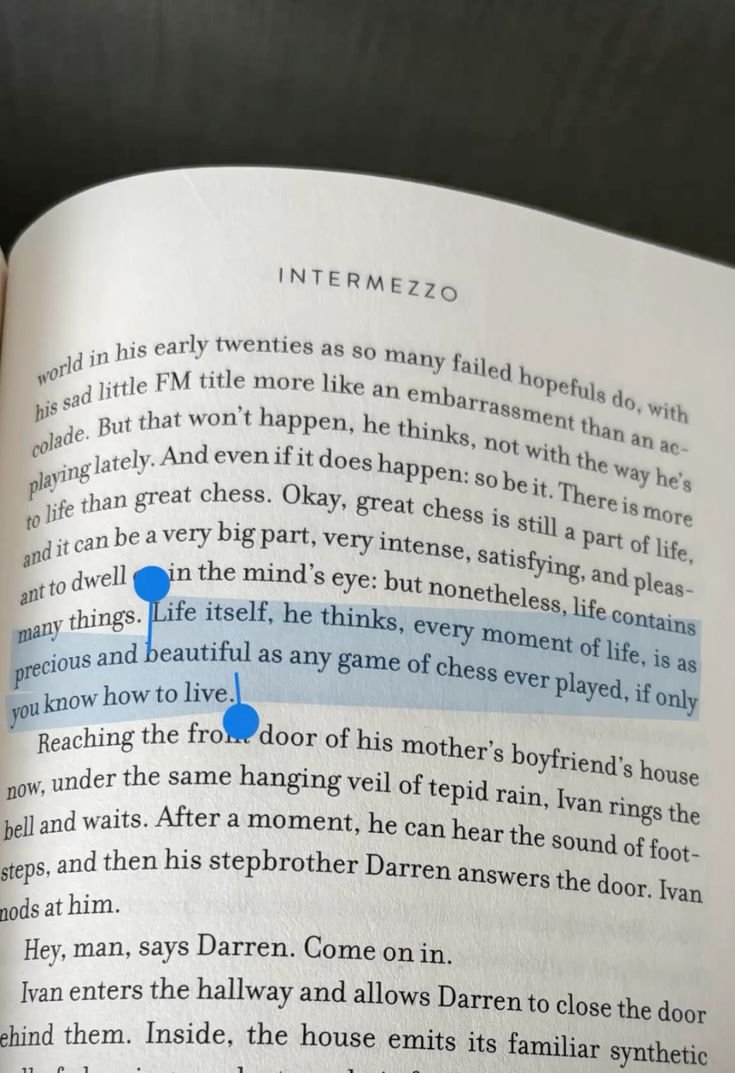

Image Courtesy of Pinterest

Peter (mentally cast as Theo James) is suspended between two women—his past and his future. His first love, Sylvia, a composed literature professor, matches his age and intellect, offering him stability and depth. With her, he debates court cases over aged wine, their lives unfolding in steady rhythm. Then came Naomi, the young and eccentric college girl, whose willingness to be dominated feeds Peter’s hollow need for purpose and control. With her, he laughs until his stomach hurts, over burnt meals and unpaid rent, caught up in a reckless, intoxicating intimacy. I disapprove of the way Rooney renders Sylvia and Naomi as flat opposites—one deep, one shallow; one missionary, one cowgirl—but for this example, it works well enough that I won’t comment further.

Peter got both girls—his past and his future, days with Sylvia and nights with Naomi. He didn’t have to choose; he got his old and his new, his beads and his bangles. It feels impossible, doesn’t it? Like life shouldn’t allow someone to have both, yet here he is.

Image Courtesy of Pinterest

Ivan (Jesse Eisenberg to me) lives in the shadow of his abandoned chess career, once a source of triumph, now something he regards as useless and immature. He craves a new certainty, something that might make him feel whole again. Instead, he drifts through remote work, awkward social encounters, and the lingering grief of his father’s death. Rooney crafts him as if he’s pacing the corridors of his own life, aimless and cornered. Then, Ivan met Margaret–an older, divorced suburban woman who is drawn to his awkward gentleness. They form a strangely explosive relationship, one that felt uncomfortable to read but satisfying to reminisce on. Ivan can’t command a room or throw a 21-year-old girl on a bed like Peter can; his love is uncertain and almost desperate. With no next move of his own, Ivan folds his life into hers, mistaking surrender for direction.

Ivan stayed with Margaret despite age—his bangle, new and dazzling—while returning to chess, his old bead. What? He got both too, and somehow, it fit.

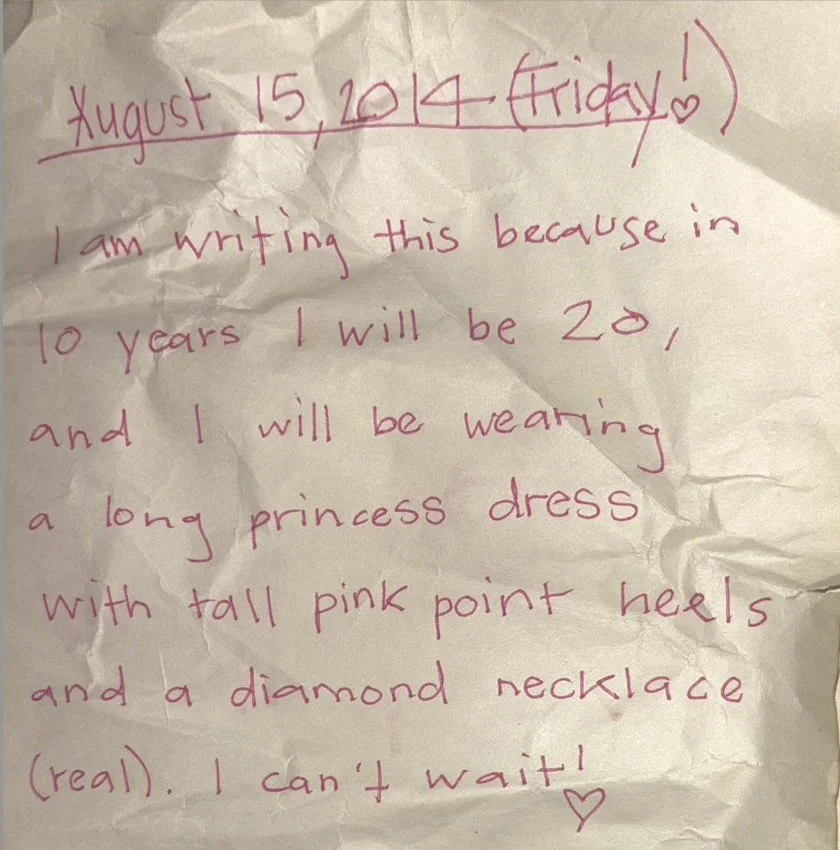

Photo Courtesy of Francesca Jaques and Pinterest

Despite the way Sally Rooney, regrettably, always makes me feel empathy for men, she masterfully turns a chess move into a metaphor in this novel. We’re all playing a game against something, and the moment you get comfortable is the moment you get bit by some ambiguous opponent who triggers your limbo.

If you’re like me, you suffocate yourself in photos from the year when your dad was still alive and your boyfriend still loved you. You let the song you used to love play a little too long, crossing the line from reminiscing to drowning. If you’re like me, you put your old beaded bracelet stack on that you used to wear like armor, like it could remind the world who you were—or who you wanted to be. Sometimes the truth slaps me in the face: bangles are heavy and impractical and stilettos will never not hurt my feet. I am no longer sixteen and unstoppable nor am I a grown girl.

Image Courtesy of Francesca Jaques

It can still be that way. Peter gets both girls. Ivan finds his way back to chess. Life doesn’t always make sense; it isn’t fair. But the gaps, the pauses, the sudden disruptions—they’re not mistakes. They’re intermezzos, and they’re yours, shaping the person you are becoming.

Strike Out,

Writer: Francesca Jaques

Editor: Olivia Evans

Francesca Jaques is an editorial writer for Strike Magazine GNV. You can find her confiding in random strangers in line for the bar- about her addiction to A24, her latest class crush who’s surely “the one,” and how girls with bangs are just cooler. If you ever want to spiral, head to the third floor of Library West and catch her with tears in her eyes, flipping through pictures of Dominic Fike. Or you can just message her on Instagram. IG: francescajaques13, email: tutijaques@gmail.com